To illustrate the problem, consider the hypothetical situation in which one person in 10 gains a profound benefit from a particular memory training app. Specifically, the current paradigm is dominated by population health and research methods devoted towards group averages, when what most of us want to know is whether something is right for us. We suggest that much of the debate, and the lack of consensus, revolves around the wrong scientific questions being asked. Still, whether one has a memory impairment or not, it is likely that, similar to diet or exercise, brain training does not benefit everyone in the same way. For vision training, there are suggestions that even elite athletes can benefit. Will it only be those who have some form of memory impairment, or can it also help those eager for self-improvement even though they are already functioning relatively well?Īlthough the jury is still out, there is evidence that short-term working memory training can provide benefits to relatively high functioning individuals, such as college students. So how do we reconcile the mixed evidence in the field and at the same time cut through the hype? We suggest that some of the confusion may result from the fact that little consideration has been given to who would benefit most from the brain training apps that are supported by research studies. Furthermore, most apps available to consumers have not undergone scientific validation at all. Despite what many apps and brain training companies will tell their customers, scientists have not uncovered the key ingredients that make an intervention effective, nor the recipes that would best address the diverse needs of those seeking help. Some affirmation of the potential for cognitive training could be seen in the FDA’s recent approval of a brain training game to treat ADHD.Ĭritics, however argue that while the concept is appealing, the overall evidence does not suffice to demonstrate that core brain processes can be truly improved. If brain training works, the field holds enormous promise to help people with cognitive impairments, and to aid individuals who are recovering from cancer or perhaps even COVID-19. That degree of difficulty and repetition, however, may be rare in daily life, which is the gap that memory apps aim to fill. Memory training apps require tracking a large number of objects while one is distracted with a secondary task (such as making mental calculations or navigating the landscape of a game). Just as athletes engage in strength and conditioning by repeatedly exercising certain muscle groups and their respiratory and cardiovascular systems, targeted repetition of memory exercises may be the key to strengthening and conditioning our memory processes. In this analogy, daily challenges, even demanding ones such as reading a detailed newspaper article or solving an algebra problem, might not be sufficiently challenging to furnish an adequate work-out for the brain. Others argue that we should consider the brain like our muscles, which can be exercised and toned. Some scientists question whether this is even possible.

The main controversies center around the extent to which the practice of these skills results in actual benefits that are consequential for your daily life. Does recalling an increasing number of digits help you remember to take your medication, do better on a school exam, remember the name of the person whom you met yesterday or even make better life choices? Undoubtedly, there is an enormous amount of hyperbole surrounding the field with many companies exaggerating the potential benefits of using their apps.

In the case of memory training, for instance, study results have been inconsistent, and even meta-analytic approaches that combine data across studies come to differing conclusions. There was even a consensus statement issued calling brain training into question, which, in turn, resulted in a counterresponse from researchers who defended it. Some researchers, including one of us, have expressed deep reservations about both its reliability and its validity. At the same time, brain training has become a profoundly controversial endeavor. The three of us, and many others, have provided evidence that carefully formulated exercises can improve basic cognitive skills and even lead to better scores on standard IQ tests.

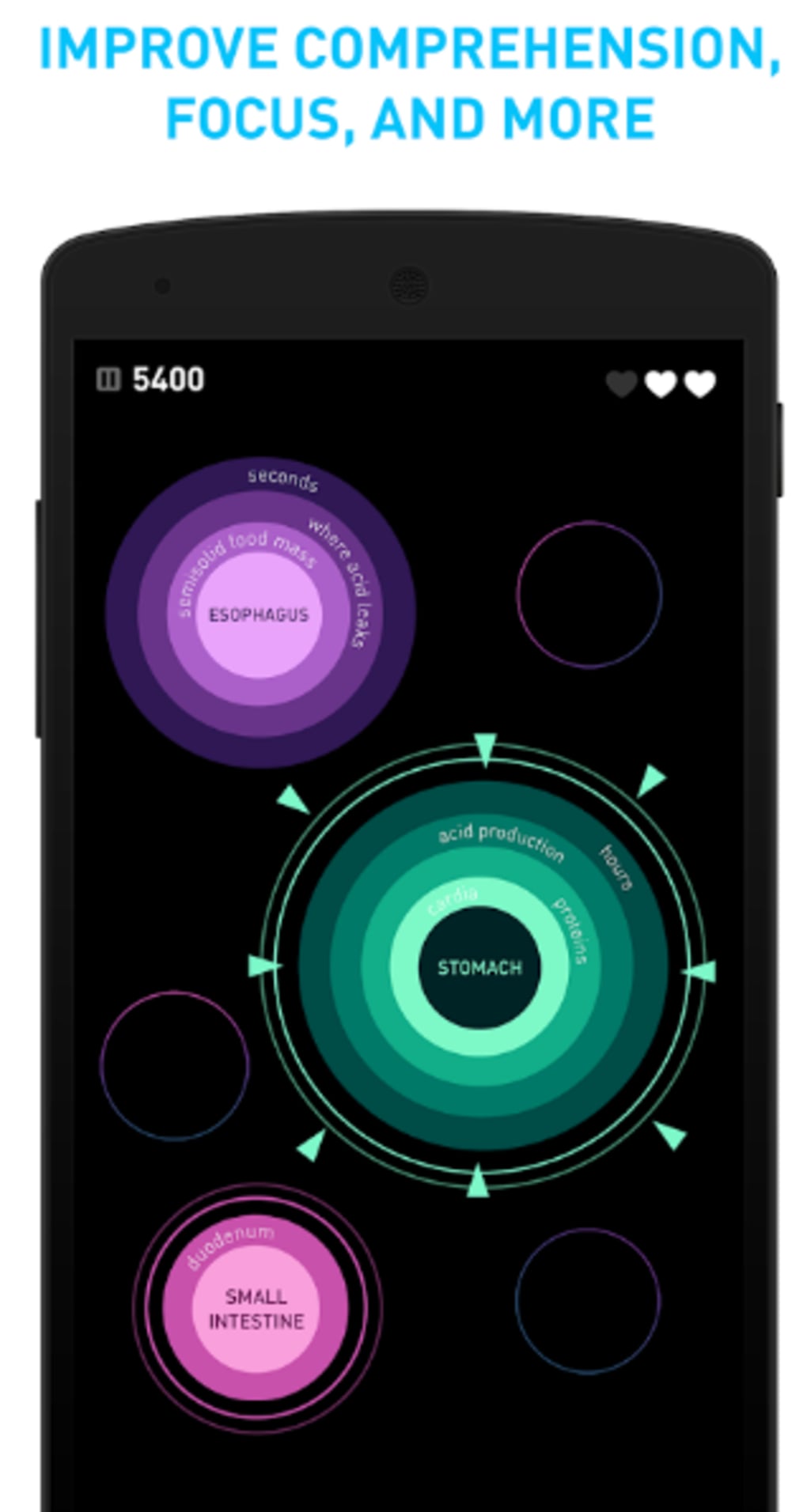

If there were an app on your phone that could improve your memory, would you try it? Who wouldn’t want a better memory? After all, our recollections are fragile and can be impaired by diseases, injuries, mental health conditions and, most acutely for all of us, aging.Ī multibillion-dollar industry for brain training already capitalizes on this perceived need by providing an abundance of apps for phones and tablets that provide mental challenges that are easily accessible and relatively inexpensive.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)